Your child’s diagnosis

Early diagnosis is good news!—it is important to pick up a child’s vision impairment early. That way you can get the help you need as soon as possible.

Finding out your child is blind, deafblind or has low vision can be a difficult time for families and whānau. It is natural to feel apprehensive about your child’s future and anxious about what is in store for you.

If your child’s condition wasn’t picked up at birth and has been diagnosed in hospital or identified later, the news may be a total shock.

You may also have found out your child has hearing loss or other needs. There may be no history of blindness or low vision or any other disability in your family.

If you are a parent who was concerned about your child’s recent development, it could be a relief to get this diagnosis because it answers some of your questions.

Whatever your situation, it is okay to experience feelings of sadness, guilt, anger or denial and to worry about how you will cope and how your child’s diagnosis impacts on the future.

“We are still grieving in many ways. But it does lessen with time. For me, it was the not knowing what he would do, what would happen to him in life. That was hard. But now I see that he will be fine—he just goes about things differently, in his own way.”

—Parent

Your feelings are personal and highly individual. How you feel will depend on many factors—your personality, your life experience, your coping style and how much support you have around you. Give yourself time to come to terms with your child’s diagnosis. Be patient with yourself and reach out for support when you need it.

Page 8

Talking can help

It helps to talk about your situation and how you are feeling with someone you trust and respect. You may want to talk to parents who have gone through something similar or professional counsellors (e.g., a Blind Foundation counsellor) with knowledge about vision loss.

Talk to other parents—it’s good to talk. Many parents say one of the things that really helped was talking to other parents who’d been through the same thing.

“Gary from the Blind Foundation and the BLENNZ Visual Resource Centre staff have become part of our family, part of our lives. They’ve been an absolute lifeline. I don’t think we’d have survived without them, especially in those early years.”

—Parent

“Be open if you can. The more open you can be, the easier things will become over time.”

—Parent

The Blind Foundation counselling service

The Blind Foundation (legally known as the Royal New Zealand Foundation of the Blind) provides a free, nationwide counselling service to children and their families from fully qualified counsellors. Counsellors will come to your home or you can visit them at the Foundation’s offices—whatever works for you.

See the Blind Foundation website

Freephone 0800-243 333

Kāpō Māori Aotearoa New Zealand Inc

Kāpō Māori Aotearoa New Zealand Inc is a national kaupapa Māori information and support service for people of all ages who are blind, deafblind or have low vision and their families and whānau. They run regional support groups and programmes focused on strengthening and sustaining the well-being of whānau.

See the Kāpō Māori Aotearoa New Zealand Inc website

Freephone 0800-770 990

Page 9

Parent2Parent

Parent2Parent is a nationwide parenting network for parents of children with disabilities. The organisation can put you in touch with parents of children who have similar disabilities to your child. They also offer training and information.

Freephone 0508-236 236

Parents of Vision Impaired

Parents of Vision Impaired (PVI) is a national parent support group. It offers parents advice, information and opportunities to meet other parents. The group also has parent support workers who can give you one-on-one help and support. PVI publishes a regular magazine and has a members-only Facebook page for families and whānau to share information and network.

See Parents of Vision Impaired website

Freephone 0800-312 019

Deaf Blind Association New Zealand

Deaf Blind Association New Zealand is a new organisation which is working within the deafblind community. They are interested in connecting with other New Zealanders who are deafblind, and sharing the latest news on issues relevant to the sector. David Wilson is the Chair of Deaf Blind Association New Zealand.

See Deaf Blind Association New Zealand

Email info@deafblindassociation.nz

Blind and Low Vision Education Network NZ (BLENNZ)

BLENNZ is an education service provider for children from birth until they are 21. BLENNZ employs Resource Teachers: Vision (RTVs) and Developmental Orientation and Mobility (DOM) specialists who work across New Zealand from a main campus, Homai Campus School, in Auckland and regional Visual Resource Centres throughout the country. They offer children and their families and whānau throughout New Zealand a wide range of services, information and advice. They will come to you at home at the time of your child’s diagnosis or visit you at your child’s early childhood education service or school—wherever suits you best.

Phone 09-266 7109 (Auckland)

Ministry of Education, Special Education

Ministry of Education employs a wide range of education specialists who visit families and whānau at home (or at a place that suits) in the early years and who work with children throughout early childhood and school as a child develops and grows older. Specialists include early intervention teachers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and educational psychologists.

See the Ministry of Education website (look for information about special education)

Freephone 0800-622 222

Page 10

Ministry of Health

The Ministry of Health funds a range of disability services for children and their families and whānau who meet specific eligibility criteria and are assessed as needing such services. Needs Assessment and Service Coordination (NASC) organisations coordinate access to Ministry of Health funded support and respite services while District Health Boards provide access to developmental and therapy support for children through child development teams. In some cases, equipment such as glasses, hearing aids and wheelchairs may be funded through the Ministry of Health.

See Disability Service on the Ministry of Health website

Freephone 0800-373 664

The Ministry of Health’s Well Child programme is a series of 13 health checks offered free to all New Zealand families and whānau for children from birth to five years. The programme includes a GP check at six weeks (linked to the six-week immunisations), as well as a health check before a child starts school.

Freephone 0800-933 922 (PlunketLine)

Your child’s vision team

It is likely you will find yourself involved with a wide range of people throughout your child’s life. At times, you might find yourself working closely with people in the health sector whose focus will be long term but may come and go depending on your child’s age, diagnosis and overall needs. These people are also likely to be more involved with the diagnosis and assessment of your child’s medical needs.

These people might include:

- family doctor (or GP)—a health professional who looks at the general health of your child and can refer you to specialists for a clinical assessment

- ophthalmologist—a specialist eye doctor who checks the health of the eye and can provide information about diagnosis and treatment

- orthoptist—a health professional who diagnoses and treats eye problems related to eye movement and coordination

- optometrist—someone professionally trained and registered to examine the eyes for visual defects, diagnose problems or impairments and recommend glasses or other corrective lenses or provide other types of treatment

- paediatrician—(a medical professional doctor) specialising in children’s health and development

- visiting neuro-developmental therapist—a specialist in child development who works with very young children.

Page 11

At the same time, you may find yourself involved with parent group representatives and people who work across the education and disability sectors. Your relationship with these people maybe more consistent, long term and cover a wide range of health, education and disability services.

These people might include:

- BLENNZ teachers or Resource Teachers: Vision—qualified teachers who support children and their parents and caregivers, providing general advice, teaching and development support

- Blind Foundation life skills specialists—keyworkers who support children and their parents and caregivers, providing general advice, counselling and support

- other Blind Foundation specialists—e.g., deafblind coordinators and recreation advisors who provide advice and support related to their area of expertise

- Kāpō Māori Aotearoa New Zealand Inc national field coordinators—specialist support workers who use a kaupapa Māori approach to help children and their whānau to access education, health and disability services

- Ministry of Education early intervention teachers—education sector specialists who provide advice and support related to a child’s learning and development

- other Ministry of Education specialists—e.g., educational psychologist, physiotherapists and occupational therapists who provide advice and support related to their area of expertise

- early childhood education and school staff—your child’s teachers, education support workers and teacher’s aides who are there to help your child develop and learn within the early childhood and school environments

- health professionals from a Ministry of Health child development team.

In this book, we refer to the group mentioned above as your child’s vision team, as their ongoing support role will help you access all the support you need throughout your child’s life.

“Having to meet so many people in the early days can be overwhelming. My advice is to take them as they come, don’t try to remember everyone’s names and, remember, they are there to help.”

—Parent

It’s important to know your child’s vision team is there to help you—regardless of who they are or which organisation they represent.

Their aim is to work as a team to build a strong relationship with you on your journey.

Page 12

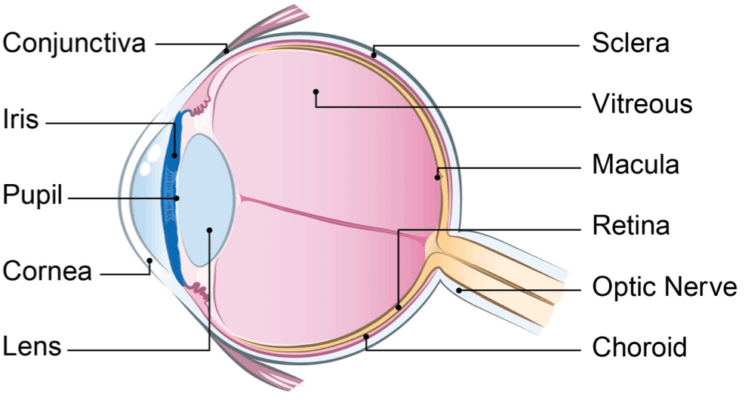

How the eye works

Understanding how the eye works and how we see is a good first step to understanding your child’s vision and the assessment process.

To see, three things need to work properly: the eye, the optic nerve (the nerve that takes information from the eye to the brain) and the brain.

It takes about six months for babies to develop much of their vision (none of us is born with fully developed vision). In this time they begin to focus, develop eye muscles, learn to scan and track, coordinate their eye movements and see the full range of colour. By the age of seven, most children have developed normal adult vision.

Share anything you notice about your child’s sight with the professionals you meet—you know your child best and you will have information that is often invaluable to others outside the home.

Page 13

Why a child’s vision is assessed

Assessments are an important way for you and the people you work with to understand how your child’s vision is influencing their overall development.

Most blind children will have some degree of vision—total blindness is rare.

Overall, an assessment will help you to:

- understand how your child is using vision to gather information about the world

- share information about your child with family and whānau and others

- understand how to support your child to develop and grow

- identify the services and support your child is eligible for and the team of specialists available to support you.

How children are assessed

The initial assessment will give you some information about what your child can see. But it often takes time to establish the full picture.

It might take months, even years, and several assessments to find out the full extent of what your child can see.

That is why it is common for specialists to use more than one method to assess a child’s vision and why they may want to see your child several times and seek the input of you and others as your child grows and develops.

Assessments can involve observation of your child in familiar and unfamiliar settings, note taking, interviewing family and whānau, as well as specialist examinations and tests.

It is a good idea to get copies of all assessment reports—keep them handy and share them with others.

Most assessments include a short report noting the specialist’s findings and things that can be done to help your child develop.

Page 14

Types of assessments

Generally speaking, there are two main types of vision assessment: clinical assessments and functional assessments.

Clinical assessments

Clinical assessments usually involve visiting an eye specialist (e.g., an ophthalmologist) at hospital.

They will:

- identify what your child likes to look at

- ask questions to understand your child’s medical history

- examine your child’s eyes

- carry out a clinical vision test (depending on how old your child is).

Clinical assessments often lead to a diagnosis and the identification of possible treatments.

Clinical vision assessments are typically done:

- in hospital by specialists, including paediatricians, ophthalmologists and orthoptists

- at your local child health clinic or by someone from the Child Development Services specially trained in the development of very young children and in identifying problems early

- at the BLENNZ National Assessment Service in Auckland by an ophthalmologist and optometrist.

Functional assessments

Functional assessments involve observing how a child uses vision to learn, move around, gain information about their surroundings and interact socially.

These types of assessments will be carried out by many of the specialists you work with to help them to develop programmes and strategies you can use at home, in an early childhood education service or out in the community.

They will:

- look at how your child uses vision

- look at how your child holds their head to look at things

- look at your child’s movement and physical response to objects.

Functional assessments often help to understand how your child is using vision, the lighting they might require, how to position things near and around your child and the sort of objects your child is able to see. As your child grows older and develops, these assessments will change as well.

Functional vision assessments are typically carried out at home by:

- visiting neuro-developmental therapists

- Resource Teachers: Vision

- Blind Foundation life skills specialists.

If your child’s vision loss resulted from an accident you can contact the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) to receive support. Ask anyone in your child’s team to help you if you don’t know what to ask for.

Health of the eye—an assessment of the health of the eye is critical to helping eye specialists diagnose visual conditions and to determine the need for medical or surgical treatment.

It is important your child has regular check-ups and that you notify your specialist if you notice any changes.

Page 15

How parents can take part

Distance vision is the ability to see objects at a distance, while near vision is the ability to see things such as text up close. Your visual field is what you can see above, below and to the side of you.

You are the people closest to your child. You know your child best. That means you have the most to contribute to an assessment.

Share anything you notice about your child’s vision and how they use their vision. Talk to specialists about what you observe. Talk to your child’s vision team about having their guidance and input throughout the assessment process.

Before any assessment gets under way, sit down with a member of your child’s vision team to find out:

- why the assessment is being done

- how the information will be used

- where you can learn more about the assessment method

- how to get a copy of the findings

- if you need to give your permission in writing.

After a clinical assessment, you and your child’s vision team might want to discuss:

- the cause of your child’s condition (in language that is easy to understand)

- the name of the condition and how it is spelled

- if the condition will stay the same or is likely to change over time

- if the condition can be treated

- if glasses or contact lenses might help when your child gets older and what, if any, role an optometrist might play as your child gets older

- any specialist treatment and anything you can do to help

- if your child’s eyes are sensitive to light

- where you can find out more about your child’s condition

- the inherited nature of the condition and if you should talk to a genetic counsellor.

After a functional assessment, you and your child’s vision team might want to discuss:

- if there is anything you can do to help your child use their vision

- if there are things you can do at home to help your child learn about the outside world

- ways to connect and communicate with your child

- different ideas for helping your child to move and develop physically.

“I say to parents you have the right to ask questions, challenge decisions, get answers and be heard—you really are your child’s best advocate.”

—Parent

“When my daughter was 16 months old, we had our first BLENNZ assessment up at Homai in Auckland. It was such a help and the specialist made me feel confident in what I was doing with my child—it put my mind at ease and helped me believe things would be okay.”

—Parent

Page 16

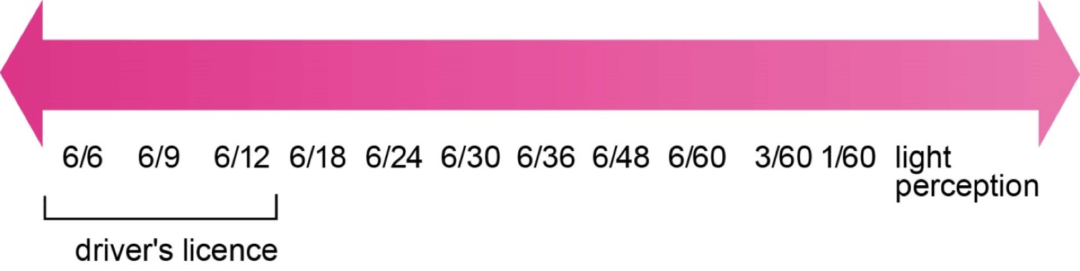

Language used to describe vision

Visual acuity is one of the terms you are likely to come across as your child is assessed and diagnosed by specialists for a vision impairment. Visual acuity is a measurement used internationally by eye specialists to describe the ability of the eye to perceive the size and shape of objects in a direct line of vision. Reduced visual acuity means reduced clarity of images and fine detail.

Normal visual acuity is expressed as 6/6—this means a person with normal vision can detect a shape or letter approximately one centimetre high from six metres away. Someone with a visual acuity of 6/24 needs to be six metres from an object to see what a person with normal vision can see from 24 metres away.

Visual Continuum

Feeling overwhelmed by too many people

At times, you may find it hard to cope with the number of people who are involved with your child—particularly if your child has several different needs, as well as a visual impairment.

If you do feel overwhelmed or need some time out, just say so. You can also say if you would like to see fewer people or would prefer to work with one person as a central point of contact.

Your child’s vision team is trained to work in a way that works best for you and your family’s needs. All you need to do is let them know where you are at.

Page 17

Communicating with your child

Every arm or leg wave, every coo, babble or smile– these are your child’s ways of communicating with you. It is important that you always try to respond—through talking and touch particularly.

Talking and touch will give your child valuable information about the world and provide them with some of the basic skills they will need to communicate.

Help your child to develop hearing and tactile (or touching) skills by:

- drawing attention to your child’s hands as you feed them (hands are precious parts of your child as givers and receivers of information)—touch them, hold and caress them, pat them, trace your child’s fingers and thumbs and (if your child is open to it) rub your child’s palms

- beginning to explore some things with your child, e.g., their bottle—its shape (rounded), texture (hard), weight (light), size and temperature

- telling your child what you are doing together as they sit on your lap to give them clues about your voice and the way you move your body.

Page 18

At home with your child

Making sure your home environment is safe and welcoming and that your child has opportunities to form an attachment with you and experience the joys of childhood is vital.

You might find these tips useful for connecting with your child and helping them learn about the world.

- Whenever you can, hold your baby (e.g., in a front pack or sling) to help your baby relate to you through touch and learn about your daily routines.

- Limit background noises as much as possible to help your child identify important sounds and language spoken nearby.

- Tell your child who is in the room and use touch signals to identify familiar people (granddad’s glasses or their brother’s hand).

- Create a regular daily routine to help your child learn to anticipate events and understand what’s coming up.

- Put toys and objects that make sound near your child’s hands so they can learn to reach for them.

- Talk to your child about what you’re doing and what is happening from their perspective, “Now you are leaving the bedroom and going outside; isn’t it warm today?”

- Once your child is mobile, keep the floors in your home as uncluttered as possible and set out the furniture to give your child room to move as easily as possible.

Talk to someone in your child’s vision team (your Resource Teacher: Vision or a Blind Foundation counsellor or life skills specialist) for ideas and advice about developing independence.

Talk to them about the different ways you can communicate with your child and help them to move about and learn about textures and temperatures, toys and play.

The Blind Foundation and BLENNZ have staff who can come to your home and talk with you about how to:

- support your child to move about and understand the world they live in

- help your child learn to do everyday activities such as eating, drinking and dressing

- check and assess your child’s vision at home

- organise vision assessments and understand reports

- develop a plan and discuss ideas that will help your child grow and develop in early childhood

- introduce you to programmes such as the Blind Foundation’s PACE programme (see opposite page for more about the PACE programme).

“We had our first BLENNZ immersion course at Homai when my daughter was just 18 months old. I met four or five different families with kids like mine, about the same age and with similar conditions. Even now, years later, we all keep in contact and give each other advice.”

—Parent

Page 19

A Resource Teacher: Vision can help you set up what they call a little room in your home—a box-like structure with everyday objects hanging from the roof and attached to the sides. Little rooms give children the opportunity to explore objects from a lying or sitting position, without interruption.

The Ministry of Social Development runs a parenting education programme called Parents As First Teachers.

The programme gives parents support and ideas about parenting. Ask someone in your child’s vision team for more information. Or check out the Ministry’s website.

See the Family Services directory website

Ask the Blind Foundation about their PACE (Parent and Child Enrichment) programme. The programme helps babies and toddlers with vision impairments to develop and learn skills such as moving, playing, eating and dressing.

Page 20

My Story:

Growing up Robert’s way

Robert Hunt wasn’t one to roll over as a small baby. He didn’t really crawl either. But he’s taken to walking with great gusto.

Meredith, Robert’s mum, says: “He’s really doing it all his way. He’s growing up entirely on his own terms. It’s wonderful, really. Just watching him reassures me he’s going to be fine.”

Robert has a rare eye condition called Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy (or FEVR, for short), severely limiting his vision in both eyes.

His condition was first picked up when Robert was about three months old.

Meredith noticed he’d startle easily and wasn’t focusing his eyes during breast feeding. Family members noticed his eyes flickered.

After a series of specialist tests Robert was diagnosed with FEVR.

“We felt devastated. One of the hardest things has been not knowing how life will be for him, because none of the usual milestones apply.

“Now he’s a little older I can see things will work out, just in a different way—in Robert’s way.”

As a baby, says Meredith, Robert didn’t smile.

“It was heartbreaking at first. But he wasn’t getting the visual cues most babies get from the people around them.”

Page 21

“So, I started to play a game with him. I’d use a soft toy to tickle his feet. Then I’d tickle his arms. I’d put his hands on my mouth and we’d giggle together—so he could feel it was okay to laugh.

“It was a lovely way to play together and bond. Robert smiles a lot now.”

At crèche, they’ve had to think outside the square too, says Meredith.

“Initially he was getting upset in the sleeping room. It was unfamiliar and confined. It was scary for him.

“The staff there are wonderful. They thought about it and set up a special area close to them, where he can hear their voices and feel more settled.”

They also designed a separate, safe corner for Meredith to use to get Robert familiar with standing, walking and using his hands to find his way around the crèche.

“It was a great idea for about half an hour,” says Meredith. “After that, Robert began reaching out to the other kids and the other kids were literally busting down the walls to get to him.

“Kids at this age just want to explore and play—and Robert’s no exception.”

Page 22

Getting involved in the blind community

There are many ways you and your family and whānau can get involved with and develop friends within the blind, deafblind and low vision community.

You’ll find there are many benefits in doing so. For parents, getting involved offers the opportunity to share information and get support. For children who are blind, deafblind or have low vision, socialising with other children like themselves can give them confidence, a feeling of belonging and the opportunity to meet children just like them.

“The best support you can get is from other parents of disabled kids. They’ve walked the walk and can talk the talk. For me, they’ve been invaluable. We share information; we encourage one another. They’ve been crucial to my survival, to be honest. Absolutely crucial.”

—Parent

Parents of Vision Impaired (PVI) offer a range of opportunities to join in and be part of the blind community. Contact PVI by phoning 0800-312 019 or check out the PVI website.

Kāpō Māori Aotearoa New Zealand Inc is another organisation offering community programmes to children and young people and their families and whānau. Programmes range from first aid training and communication to Māori tikanga and peer support. Contact Ngāti Kāpō by phoning 0800-770 990 or check out the Kāpō Māori Aotearoa New Zealand Inc website.

Paying for services

Understanding the services available to you and your child and who pays for what can be a challenge for anyone. As a general rule, you will find that most services to support your child’s vision are free until your child leaves school. In New Zealand, most parents make use of the free public health and education systems. Some parents choose to pay for private professional support such as the services of a private opthamologist. Other parents prefer to do both.

Needing time out

Caring for a child who is blind, deafblind or has low vision can be hard work. At times, you may find you need a break. That is where the Ministry of Health funded respite service may be able to help. Available through the Needs Assessment and Service Coordination (NASC) service (following an assessment), it offers parents and carers regular time out, time out during an emergency or time out in a one-off situation simply because you need it. Work and Income also offers the Child Disability Allowance to the main carer of a child who needs constant care and attention because of a disability. Talk to your child’s vision team or your GP to find out more about these services.

“We’re looking at the carer’s subsidy. It’ll give us time out just to talk—to talk about our baby, to talk about the family and, maybe, to talk about anything “but” those things …”

—Parent

Page 23

Other support

If your child has a complex needs, you may be able to get funding from the Ministry of Health for equipment such as a wheelchair or standing frame your child might need at home.

To find out more, contact your GP or your local Child Development Services to ask about getting an assessment with an Equipment and Modification Services (EMS) Assessor. You can also find out more from the Ministry of Health’s website. Go to Ministry of Health website (search using the terms “equipment and modification services”).

Ministry of Health funding is also available for travel assistance to and from hospital, specialist appointments and your child’s early childhood education service. Talk to someone in your child’s vision team to find out what is available. Visit the Ministry of Health’s website (search using the terms “National Travel Assistance”).

Preparing for early childhood education

Preparing yourself and your child for an early childhood education service can be hard for many families and whānau. It can trigger feelings of sadness and apprehension about the future.

These feelings are perfectly natural. It can help to take time out at times like these—even a gentle walk can be good for clearing the head. It can also help to talk about how you’re feeling with a Blind Foundation counsellor.

Government funding for 20 hours of early childhood education—all services offer 20 hours to children from the age of three. Talk to your child’s vision team to find out more.

A Glasses Subsidy from the Ministry of Health is available to children 15 years and under with a Community Services Card or High Health Use Card. Funding contributes to assessment, lenses and frames. For more information, contact 0800-171 981, talk to someone in your child’s vision team or check out the Ministry’s website. Go to the Ministry of Health (search using the terms “spectacle subsidy”).

A Contact Lens Subsidy is available from the Ministry of Health to children who for medical reasons cannot wear glasses (and who meet criteria). For more information, check out the Ministry’s website. Go to the Ministry of Health (search using the terms “contact lens subsidy”).

Page 24

Will your child be okay?

Every child is different, so it is hard to tell just how your child will respond to the experience of going to and starting early childhood education.

For most children, however, it provides an opportunity to learn to play with other children and get used to moving about confidently in a different environment. All these skills and knowledge are valuable and will help your child grow, develop.

Your love, acceptance and support as your child makes the transition out into the world will help.

“The great thing about places like kindy is that kids don’t care or notice disabilities. Chances are your child will be simply accepted as one of the gang …”

—Parent

Choosing an early childhood education service

New Zealand has many types of early childhood education services to choose from. Each type has its own way of working with children and with families and whānau.

Some offer all-day education and care; some offer only a part-day service.

Generally speaking, services fall into two main categories.

- Teacher-led—where registered teachers provide the education and care, e.g., kindergartens and early childhood education centres.

- Parent-led—where parents, families and whānau provide the education and care for their own and other children, e.g., playcentres and kōhanga reo.

If you’re not sure about the service best suited to you and your child, talk to someone in your child’s vision team for advice and guidance. You might like to visit a few services before deciding on the right one. Talk to the service and your child’s vision team and book a time to go. Ask for time with the people in charge so they can answer any questions you may have.

Te Whāriki is the Ministry of Education’s early childhood curriculum policy statement. Te Whāriki is a framework that focuses on learning partnerships between the child, teachers and whānau based on the child’s needs and sociocultural context.

Page 25

Settling in

Although many children settle happily into a new environment, being away from you and other family can be difficult for some children.

Here are some of the things you can do to help your child settle in.

Visit the service several times before you leave your child for the first time. Give yourself the chance to observe how teachers relate to your child and other children, what the routines are and how their programme works.

“It’s tempting to keep young ones wrapped up in cotton wool—particularly when they’re little. My advice is don’t do it. Resist the temptation. The best thing you can do is to encourage and support them to get out and explore the world.”

—Deafblind adult

Don’t hesitate to ask if someone in your child’s vision team can go with you.

Someone from your child’s vision team will support you to talk to your child’s teachers about:

- your child’s vision loss—from the diagnosis, through to what your child can see and how it impacts on your child’s ability to move about and relate to others

- areas of development, such as encouraging independence

- tips on communicating with your child and making them aware of what is happening around them using speech and touch

- the equipment and technology your child uses (if any)—show them how it works, how it needs to be maintained and give them any troubleshooting tips they might need

- the important people in your child’s life and any important things going on right now that are having an impact on them

- things your child likes, dislikes, is good at, finds a challenge, needs help with, can get upset about and can do independently

- the need for good lighting and tidy, clear pathways your child can use to move safely from place to place.

Page 26

Getting the right support

The main organisations available to give you help and support while your child is in early childhood education are:

- BLENNZ—they will help you choose a service and help your child make the move from home to early childhood education. They will support the parents and teachers working in the service to know and understand your child’s learning and development needs. BLENNZ Resource Teachers: Vision may also teach your child additional skills related to understanding concepts, communication, vision, living, movement and social development to support your child’s growth and development.

- Blind Foundation—they will help your child learn to do everyday living tasks and develop strong relationships with others in their new environment. They are there for you, as well, to help you adjust to the changes occurring for you and your child.

- Ministry of Education—the Ministry’s early intervention specialists will work with you (depending on the needs of your child), the Resource Teacher: Vision and your child’s early childhood educators to help your child to develop and learn alongside their peers. Early intervention specialists know about child development and how to support teachers to include children who are blind, deafblind or have low vision in the early childhood programme.

How will you know if things are working well?

Take time to talk to people at your child’s early childhood education service. Raise any concerns you have about your child’s learning and development. Have a chat with your child’s teachers about the different strategies they use and the different things they emphasise for your child. Pick up the phone or email them or ask someone in your child’s vision team to organise a meeting where you get together and discuss what is happening.

Helping your child to develop and learn

There are many ways you can keep up with your child’s learning and development. You and your child’s vision team can talk about:

- keeping a written or digital home to early childhood service diary that describes what your child did during the day and how they responded (completed by staff at your child’s service)—you then add information about what happened at home and share it with staff the next day

- developing a written plan for your child that identifies their learning and development goals and sets out how the goals might be achieved, by who and with what support (these are sometimes called individual development plans)

- reading learning stories created by your child’s early childhood education service teachers that show what your child is learning and how they are developing. These can be a wonderful tool for thinking about what your child is achieving and helping your child develop confidence.

Page 27

Preparing for school

Getting ready for school is another big step in your child’s life and another big step for you and your wider family and whānau. Some of those familiar feelings of sadness and apprehension may resurface. You may start feeling anxious about how your child will cope at school. Naturally, you want the best for them—but will they be happy?

The best thing you can do is talk to and plan with your child’s vision team—they know this can be a tricky time and they will know how to support you.

Give yourself and your child’s vision team 12 to 18 months to plan.

Together, think about:

- how to plan for your child’s transition

- choosing a school (it is a big decision)

- where to find out more about a school (e.g., by looking at their website, the latest Education Review Office (ERO) report and by talking to other parents)

- the Ongoing Resourcing Scheme (ORS), which provides additional time and assistance from a specialist teacher and a teacher’s aide, and ongoing specialist support or oversight from the Ministry or Ministry funded providers. There are two levels of ORS support, high and very high

- changing school property (the earlier you, your child’s vision team and your child’s school think about any changes, the better)

- meeting with the school to share information, discuss your child’s strengths and needs, and identify any additional support they can offer

- applying for any assistive technology your child may need.

“Don’t be surprised if you feel quite emotional at times. School life can be a trigger in my experience. Just when you think you have it all sussed, those old feelings can sneak up and bite you again …”

—Parent

“Making that change to school isn’t easy. This is when you part company with your child and let them loose in the world without you. It is a scary time and it can be a time when problems surface. Make sure you have support around you and someone you can talk to.”

—Parent

B4 School Check

B4 School Check—is a nationwide programme offering a free health and development check for four-year-olds. The programme includes vision and hearing screening.

Freephone 0800-933 922 (PlunketLine)

My Story: Support people give mum confidence about the future

Parent Justine Edwards says it’s hard to single out the one specialist who’s made the biggest impact on her young six-year-old daughter’s life.

There’ve been so many. And each one has had an important role to play—albeit in a relatively short period of time.

Justine’s daughter, Giana, is blind. Her formal diagnosis, revealed through an MRI scan at 11 months, is “bilateral optic nerve hypoplasia, septo optic dysplasia, with an absence of a septum pellucidum”.

“It’s a mouthful to say, I know,” says Justine, “but essentially it means Giana’s optic nerve didn’t form properly as a baby, causing blindness. It also means she takes a little longer to learn things and to communicate.”

When Giana was six weeks old, Justine and her Plunket nurse noticed Giana’s eyes weren’t fixing on or following things as they should.

A referral to an eye clinic led to a visit to a hospital ophthalmologist, which, in turn, led to referrals to the Blind Foundation and the Blind Low Vision Education Network NZ (BLENNZ).

Over the past few years, Justine and Giana have seen counsellors, orientation and mobility instructors, early childhood education and hydrotherapy specialists, paediatricians, a Resource Teacher: Vision (RTV) and the BLENNZ Homai assessment team in Auckland.

Justine has signed up with Parents of Vision Impaired (PVI), attended PVI conferences and is a frequent attendee of BLENNZ immersion courses.

Page 29

“When I think of all the people we’ve met, it can seem overwhelming. I’d say Giana and I would’ve seen more than 20 different specialists over the past six years.

“Yet, to me, I’ve been so grateful to have the support. Yes, I’ve got my own whānau, which is fantastic. But all this additional support that I can tap into is amazing.

“I don’t know how I would’ve survived without Giana’s Resource Teacher: Vision. And through PVI, I’ve met incredible parents who’ve helped me accept things and have become my support network.

“At my first BLENNZ immersion course, when Giana was 18 months old, I met four or five families with kids around the same age as Giana, with the same condition. Even now, we all keep in contact and give one another advice.”

Justine says the benefits for Giana have been huge, too.

“She’s a wonderful wee girl and she’s progressing well thanks to all the support around us.”

What are some of the stand-out milestones?

“Well, she’s overcome a resistance to touch, new people and unfamiliar surroundings. That’s a biggie. And she’s gone from crawling to walking, while starting to play and develop friendships.

“These days I feel much more confident about what the future holds for Giana. Yes, things are challenging, but there are some incredible people there to help her succeed and that means a lot.”

Page 30